|

| These Were Placed Everywhere Along the Route -- Can You Make It Out (photo Drew Smith) |

It is appropriate to celebrate our Independence Day in France since-- lest we forget -- without France we would have unlikely won our independence in the first place. Instead of American Flags, the posts and buildings were covered with yellow for -- what else -- the Tour de France.

|

| Hotel de Provence, Our Hotel , Bathed in Mediterranean Light and On the Path of Le Tour |

But this is not just any Tour... this is the 100th Anniversary of the Tour de France, and it was coming just too close to us and our Spanish Hemingway travels not to experience.

|

| We Awoke to Sounds of Street Sweepers and Tow Trucks Outside My Hotel Room, Clearing the Streets for the Race (notice the yellow "arrow sign" to the right of the planter -- that is for the cyclists) |

I am a fan. This time of the year my family knows better than to pry me away from the tv during the nightly replays. I like the drama and the human stories and the French countryside and the history of it all.

|

| My Morning Newspaper -- "They Are Here!" |

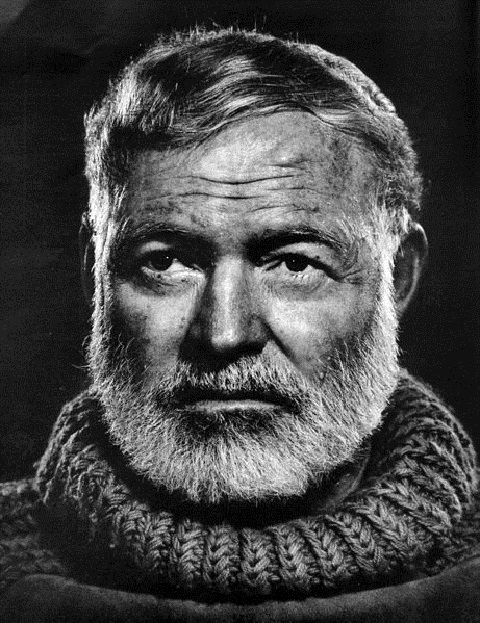

Besides, Ernest Hemingway was an avid fan of cycling races. When he lived in France he once wrote a little about some riders taking part in the tour, and cycling was his real love as a spectator before he discovered the Bull Fights. I wonder how famous the Tour would be today if he had focused on it instead of having his head turned at Pamplona.

|

| Our Awesome Room and Balcony |

Unfortunately, I forgot to pack my US Flag, which I was intending to unfurl on the large balcony you see above as the riders passed us by. It was also going to be how people back home would identify us from the helicopter shots. I knew from years of watching that, on July 4th, the helicopters always focus on the US Flags in the crowd... Oh well. Maybe next time. Absent the flag, I decided that we would watch the greatest cycling event in the world the way they do it in France.

|

First, A French Breakfast (Nutella, Madeleine, Croissant, Cheese, Prosciutto, of course)

|

Have you ever wondered how the French watch Le Tour? They find a cafe, put it on the television, stake out a position on the route from which they can see it, and then go back to their table after the bikers go through and watch the rest of it on French TV.

|

| All the Talk in the Paper and in the Cafes were of the French Riders |

|

| Dad & the Owner Looking at a Map |

|

| We Found Our Cafe & Staked It Out |

|

| Our View of the Straight Away After the S Curve, Before the Race (photo Drew Smith) |

The First Sign of the Tour is the "Parade" of Sponsors and Others Coming Through with Interesting Cars Throwing Out Goodies to Everyone on the Street Like Santa Throwing Candy -- visors, t shirts, wrist bands, newspapers, food, you name it.... They Would Stop and Dance and Sing for the Crowd... It was fun!

The First Sign of the Tour is the "Parade" of Sponsors and Others Coming Through with Interesting Cars Throwing Out Goodies to Everyone on the Street Like Santa Throwing Candy -- visors, t shirts, wrist bands, newspapers, food, you name it.... They Would Stop and Dance and Sing for the Crowd... It was fun! |

A bottle of local wine, cheese, and fresh French bread being served with the Tour Special -- in our case the Beef Bourguignon- ooh la la!

As we drank and ate, and drank and ate, I would go inside join others to check out the progress of the race on TV, as it headed towards us from the town of Aix En Provence on its way to Montpelier -- the end of Stage Six . I found one person (yes one) who understood English, and one waiter who sort of understood my broken French sometimes, maybe. Note to self -- study harder before going back.

The big news was about the French rider that had fallen in a bad accident and gotten too far behind... it was even rumored that he was getting out. He was the Great French Hope of that year (there is one every year).

|

| Waiting Between Parades of Sponsor Cars -- Dad is Behind the Hedge-It was Actually Packed (photo Drew Smith) |

As the crowds continue to build, I slip in and out (between sips of French wine) to watch on French television as they get closer. I ask the one Frenchman who speaks English and he says it is close now.

|

| This Was Clearly The Favorite Team of This Crowd -- So We Joined In |

We go to the curb and find a spot, getting ready for the first signs of their approachment... and here it is. The French Police come through first, followed by the media vans and busses, including the big trucks with the Satellite Dishes, and we begin to hear the helicopter overhead.

About this time, I am really sad I did not bring the flag. Then the motorcycles come (with the cameras), and you know it is close. The crowds move in, and I notice my French friend speaking English, but it is to someone else, a girl standing next to me. Hmnnn... but too late now to make introductions, they are almost here!

|

| The Police Came First to Clear the Route (photo Drew Smith) |

|

| The Motorcycles with the Cameras (Photo Drew Smith) |

And then the first rider came and then...whoosh... S Curve or No curve, they road by just inches away in a swoosh of multi-colored jerseys that almost blended together. I searched for the Yellow Jersey and quickly caught it -- good. And they were gone. Yep, just that fast. The S Curve? HA! No challenge at all.

|

| The Breakaway! (All Bike Race Photos Drew Smith) |

|

| Playing Catch-up After a Crash-The Last Rider (photo Drew Smith) |

|

| (Photo Drew Smith) |

|

| (Drew Smith Photo) |

Later, Drew would find and download on Facebook the official video of them going through Tarascon, and you can see my bright orange shirt standing next to Dad as I cheered them on. Even that was a split second.

You see a summary of Stage Six at this link and at 1:21 you can see my orange shirt cheering them on (if you have a really good computer...look fast too lol). Here is: http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x11j9u8_en-summary-stage-6-aix-en-provence-montpellier_sport?start=9 Like I said, you have to really look fast. Even I have a hard time seeing me and I know where I am. But it is a good review of Stage Six anyway.

|

| See the Green Hand on the Left Under the Lamp? I am Over There Somewhere (photo Drew Smith) |

|

| On Their Way to Montpelier (photo Drew Smith) |

This is why they say if you want to see the riders up close, you had better head for the Pyrenees. Unfortunately, that was not an option on this trip. Maybe next time.

|

| The French Fulbright Teacher, Far Left, & our Two Arkansas Expat Ft Smith Friends in the Middle! (photo Drew Smith) |

As we were about to head back to the Cafe and the wine, I remembered the English speaking tourist standing next to me. She had an accent. She had a Southern accent. She looked at me at the same time with the same thought..."where are you from?" she asked. "The US" I replied. "Really, so are we, what state?" "Arkansas"... "NOOOO WAY!!!" she nearly yelled, "so are we!!!!!!!! Ft. Smith!"

Remember the Frenchman in the cafe who spoke English? It turns out that he is a Fulbright Scholar and was their teacher at UA Ft. Smith, and they were with him staying at his home to watch the tour.

We talked for awhile, took pictures with everyone's phones, and I wished them a Happy 4th, expressing relief to find another American on our greatest holiday. They had completely forgotten what day it was... so my patriotic duty was to remind them, of course. It was easy to forget, to be sure. They agreed the flag would have been a great idea.

|

| Crossing the Rhone -- What Most of You Saw from the Helicopter (Drew Smith Photo) |

What are the odds that out of thousands of people that day, lining the routes of the Tour de France, that the only three people we met who even spoke English much less were from the US, much less Arkansas, just happened to be standing right next to us!?

|

| The Tarascon Skyline on the Day of Stage Six (Drew Smith Photo) |

The Fulbright Scholar had just returned to his hometown and, he said, wanted to show them how to watch the Tour de France "the French way," at the local cafe.

|

| (Drew Smith Photo) |

So, just another 4th, with a couple of Arkansans, in a village in the South of France, with thousands of others on the 100th Anniversary of the Tour de France, celebrating Independence Day, the Arkansas Expat en France way!

Next up? Tarascon is also the home of St. Martha, and she is buried here. I have some incredible photography of her tomb and her church, as well as castles, and a Roman aqueduct (pictures courtesy of Drew Smith).

Until then, Au Revoir!

VIEW GALLERY

VIEW GALLERY